Report to: Board of Health

Meeting Date: March 2, 2016

Report Number: BOH Report – BH.01.MAR0216.R06

Prepared by: Jennifer MacLeod, Manager, Health Analytics

Approved by: Andrea Roberts, Director, Family Health & Health Analytics

Submitted by: Dr. Nicola Mercer, Medical Officer of Health & CEO

Recommendation(s)

(a) That the Board of Health send a letter to the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development requesting that the federal government study the merits of a basic income guaranteeas a policy option for reducing poverty and as a measure to improve the health of all Canadians.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A Basic Income Guarantee is intended to ensure universal income security.1 There are currently individuals and families who are living in poverty in Wellington County, Dufferin County and the City of Guelph.2 There have been widespread advocacy efforts to support an investigation into and consideration of a Basic Income Guarantee for all Canadians. Pilot studies have demonstrated that Basic Income Guarantee initiatives can achieve intended outcomes.3

BACKGROUND

Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) is an income transfer from government to citizens that is not tied to labour market participation.1 The objective of basic income guarantee is universal income security.1 A basic income guarantee ensures that income for all individuals is at a level that is sufficient to meet basic needs and live with dignity, regardless of work status.4 There are different models of basic income guarantee and it is known by other names such as Guaranteed Annual Income (GAI), Basic Annual Income, Guaranteed Liveable Income, and Citizen’s Income.4 A Basic Income Guarantee has the potential to alleviate or even eliminate poverty.5

One of the proposed models of Basic Income Guarantee is the negative income tax model (NIT). The NIT model depends on the tax system to administer income. Within this model there are three basic elements:

The benefit level – which delineates the maximum benefit payable to an individual

The reduction rate – which is the amount by which the benefit is decreased for additional income that exceeds the maximum allowable level

The break-even rate – which is the amount of income at which an individual will receive no benefit because the reduction rate has reached 100% 6

Glen Hodgson, Chief Economist of the Conference Board of Canada stated that there are solid economic, fiscal and social reasons to give a guaranteed annual income serious consideration. He outlined three main advantages:

Its approach to addressing poverty would reduce public administration by streamlining existing social welfare programs into one universal system. The system used would be the already existing tax system.

Earned income for the working poor could be taxed at low marginal rates. This would provide a strong incentive for recipients to work to earn additional income.

Through reducing the prevalence of poverty, a guaranteed annual income could create better health outcomes and therefore reduce health care spending. 7

Senator Hugh Segal has enumerated other compelling reasons to support a Basic Income Guarantee. He believes that it will result in supporting people to become productive, taxpaying, full participants in our economic mainstream. In contrast, continued societal poverty will result in “serious economic, stability and social cohesion costs that are not sustainable.” In addition, he points out that a Basic Income Guarantee would result in significant economic savings from reducing the administration costs of current systems.8

A Basic Income Guarantee has many advantages over minimum wage. It is financed through the tax and transfer system. Those who earn more money pay more for it. It is available whether an individual is working or not. In contrast the minimum wage is only of benefit to those who have a job and the cost of minimum wage is borne entirely by employers. As a result, employers may hire fewer workers or provide fewer hours of work. 9

In 2011 it was estimated by the National Council of Welfare that it would cost $12.6-billion to top up the 3.5 million Canadians living under the poverty line. At that time the amount was less than five percent of the federal budget. It was also less than half the cost imposed on the economy by poverty and its effects. 10 Allowing poverty to continue is far more expensive than investing to improve the economic well-being of those who are impoverished.4 The cost of poverty has been estimated at 5.5 to 6.6 percent of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is attributed to costs of health care, criminal justice and lost productivity. Canada’s GDP is currently in the range of $1.5-$2.0 trillion a year. As a percentage of the current GDP, poverty costs are calculated to be in the range of $82-$132 billion per year.4

“Given that basic income is designed primarily to bring individuals out of poverty, it has the potential to reduce the substantial, long-term social consequences of poverty, including higher crime rates and fewer students achieving success in the educational system.”4

The Low Income Measure After Tax (LIM-AT) identifies individuals living in households with an income that is lower than 50% of the median adjusted income for all households of the same size in that year. The adjustment for household size reflects that fact that a household’s needs increase as the number of household members increases, although not by the same proportion per additional member. For 2010, the LIM-AT threshold for a household of two people was $27,521. That same year, the LIM-AT threshold for a household of four people was $38,920.11

Living below this threshold is an indication of poverty. There are individuals and families who are living in poverty in Dufferin County, Wellington County, and the City of Guelph. The National Household Survey data shows that 10.5% percent of WDG residents live in low income circumstances as measured by the LIM-AT (10.1% in Dufferin County, 8.4% in Wellington County and 12.1% in the City of Guelph).2 Since 2008, Ontario Works caseloads at the County of Wellington and Dufferin County have risen by approximately 60% and 42%, respectively.12, 13

Poverty has a negative and lasting impact on health and well-being. Income may be the most important determinant of health as it influences health related living conditions.14 A Wellesley Institute report presented compelling evidence that low income almost inevitably ensures poor health and significant health inequity in Canada.15 People living in poverty use health services more frequently and often are more seriously sick or injured. Low income results in poor health and is attributable to 20% of total health care spending in Canada.16 Children who live in low income households are particularly affected. They are more likely to have a range of health problems throughout their life, even if their socioeconomic status changes later in life.16

Canadians with the lowest incomes are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions such as diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease, and to live with a disability. The Wellesley Institute study, Poverty Is Making Us Sick offered a comparison between the highest and lowest income quintiles among Canadians and found that the lowest quintile had double the rates of diabetes and heart disease than those in the highest one. Those in the lowest quintile were 60% more likely to have two or more chronic conditions, four times more likely to live with disability, and three times less likely to have additional health and dental coverage.15

Research conducted across multiple countries found that countries with higher rates of income inequality had higher levels of health and social problems across all income levels. This pattern was consistent and included health issues such as mental illness, higher levels of obesity and lower life expectancy, educational achievements such as math and literacy scores, and community issues such as violence.17

Politicians have acknowledged the benefits of a Basic Income Guarantee. The Senate of Canada in 2009 released a report on poverty which called for a study on the costs and benefits of a basic income supplement.18 Conservative Senator Hugh Segal has long been a proponent of a Basic Income Guarantee. In 2012 he wrote that, “if the federal tax system topped up everyone who was beneath the poverty line to above it, there would be no Canadians eligible for provincial welfare.” As a result the lowest income Canadians “would not occupy homeless shelters, prisons, court rooms and mental hospitals disproportionately to their percentage of the population, because they would be liberated from poverty-caused pathologies by having a basic income guarantee.” 19

At a 2014 convention, Liberal party members passed a policy resolution pledging to create a basic annual income. Priority Resolution 100: Creating a Basic Annual Income to be Designed and Implemented for a Fair Economy resolves “that a Federal Liberal Government work with the provinces and territories to design and implement a Basic Annual Income in such a way that differences are taken into consideration under the existing Canada Social Transfer System.” 20

Minister of Families, Children and Social Development, Jean-Yves Duclos, a veteran economist, has a mandate to come up with a poverty-reduction strategy for Canada. He stated that he appreciates the principles behind the idea of a guaranteed income, “greater simplicity for the government, greater transparency on the part of families, and greater equity for everyone.” 21

There have been widespread advocacy efforts to support an investigation into and consideration of a Basic Income Guarantee for all Canadians. Public Health agencies recognize that poverty and income inequality have well-established relationships with adverse health outcomes. In the Public Health sector, resolutions have been passed by the Association of Local Public Health Agencies (alPHa) and the Ontario Public Health Association (OPHA), calling for governments to “prioritize joint federal-provincial consideration and investigation into a basic income guarantee, as a policy option for reducing poverty and income insecurity and for providing opportunities for those in low income.”6 Prior to the last federal election the Canadian Public Health Association released a fact sheet calling on the next federal government to take leadership in adopting a national strategy to provide all Canadians with a basic income guarantee.22

In a 2014 report the Canadian Association of Social Workers proposed the development of a basic income to encourage pan-Canadian income, social and health equity.23 In August 2015, prior to the Federal election, members of the Canadian Medical Association passed a motion in support of a basic income guarantee.24 The motion passed with a sizeable majority.

Support for a Basic Income Guarantee has also emerged from municipalities. In December of 2015 the City of Kingston passed a resolution advocating for the federal and provincial governments to consider, investigate and develop a basic income guarantee for all Canadians. The City of Kingston resolution was forwarded to all municipalities in Ontario with a request that they consider supporting the initiative. To date the resolution has been endorsed by the cities of Cornwall, Belleville, Pelham, Peterborough and Welland.4

ANALYSIS/RATIONALE

One of the only major studies on Basic Income Guarantee in a high-income country that examined outcomes beyond labour market effects was conducted in Canada in the 1970s. This study, “MINCOME”, was conducted in the province of Manitoba between 1974 and 1979. The research design involved selecting families from two communities: the city of Winnipeg, and the small rural community of Dauphin, Manitoba. A unique design element in the study was that Dauphin was a saturation site; everyone was entitled to participate in the study. About a third of Dauphin families qualified for MINCOME stipends at any point in time. Families from other small, rural communities were selected as study controls for the Dauphin families.3

One of the advantages of the saturation site was that it reproduced the conditions that would be present in a universal program. It was believed that this would result in a greater ability to understand administrative and community outcomes in a less artificial environment. In addition, a saturation site can result in a “social multiplier effect” - outcomes that are stronger than one might expect because the broader community benefitted from changing social circumstances.3 Details of the MINCOME stipend are described:

“The Dauphin cohort all received the same offer: a family with no income from other sources would receive 60% of Statistics Canada low-income cut-off (LICO), which varied by family size. Every dollar received from other sources would reduce benefits by fifty cents. All benefits were indexed to the cost of living. Families with no other income and who qualified for social assistance would see little difference in their level of support, but for people who did not qualify for welfare under traditional schemes – particularly the elderly, the working poor, and single, employable males – MINCOME meant a significant increase in income. Most important for an agriculturally dependent town with a lot of self-employment, MINCOME offered stability and predictability; families knew they could count on at least some support, no matter what happened to agricultural prices or the weather. They knew that sudden illness, disability or unpredictable economic events would not be financially devastating.”3

At the end of the four-year study virtually no analysis was done by project staff, and a final report was not produced. This is attributed to a change in the intellectual and economic climate. There were also changes in both the federal and provincial governments.3

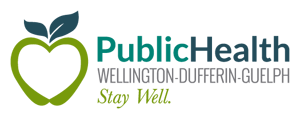

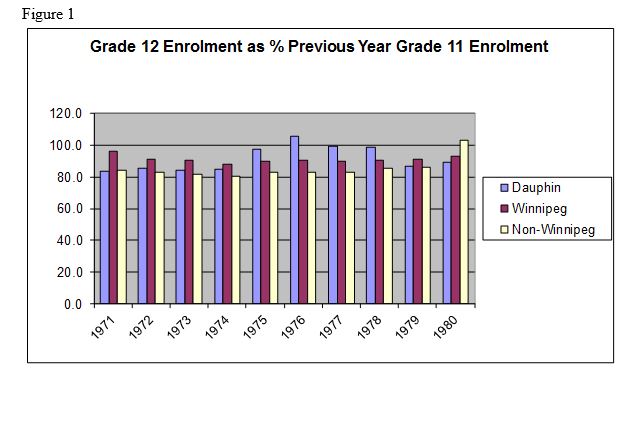

Dr. Evelyn Forget, an economist and professor at the University of Manitoba, conducted an analysis of the MINCOME study in 2009 and published her findings in 2011. She was interested in determining what impact MINCOME may have had on population health. The results were impressive. The MINCOME study demonstrated higher rates of school completion (Figure 1), and a reduction in hospitalizations (Figure 2).25

Data Table for Figure 1:

No data table available.

Data Table for Figure 2:

No data table available.

Ontario Public Health Standards

“Addressing determinants of health and reducing health inequities are fundamental to the work of public health in Ontario. Effective public health programs and services consider the impact of the determinants of health on the achievement of intended health outcomes.” (p.2)27

WDGPH Strategic Commitment

| DIRECTION | APPLIES? (YES/NO) |

|---|---|

| Health Equity: We will provide programs and services that integrate health equity principles to reduce or eliminate health differences between population groups. | YES |

| Organizational Capacity: We will improve our capacity to effectively deliver public health programs and services. | NO |

| Service Centred Approach: We are committed to providing excellent service to anyone interacting with Public Health. | NO |

| Building Healthy Communities: We will work with communities to support the health and well-being of everyone. | YES |

Health Equity

A Basic Income Guarantee will ensure that all individuals living below an identified income threshold will be supported at a level that is sufficient to meet basic needs. There is strong evidence that reducing poverty will result in improved long term health outcomes.

Appendices

None.

References

1. Pasma, C., and Mulvale, J. Income Security for All Canadians: Understanding Guaranteed Income. Ottawa: Basic Income Earth Network Canada; 2009. Available from: http://www.cpj.ca/files/docs/Income_Security_for_All_Canadians.pdf

2. Statistics Canada. National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Ottawa. 2013.

3. Forget, E. The Town With No Poverty: Using Health Administration Data to Revisit Outcomes of a Canadian Guaranteed Annual Income Field Experiment. University of Manitoba. [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2016 Feb 16] Available from: http://public.econ.duke.edu/~erw/197/forget-cea%20(2).pdf

4. Basic Income Canada Network. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.basicincomecanada.org

5. Young, M., and Mulvale, J. Possibilities and Prospects: The Debate Over a Guaranteed Income. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2009. Available from: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/possibilities-and-prospects

6. Hyndman B, Simon L. Basic income guarantee: backgrounder. alPHa-OPHA Health Equity Workgroup; 2015

7. The Conference Board of Canada. A Big Idea Whose Time Has Yet to Arrive: A Guaranteed Annual Income [Internet]. 2011 [Updated 2011 Dec 15; Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.conferenceboard.ca/economics/hot_eco_topics/default/11-12-15/a_big_idea_whose_time_has_yet_to_arrive_a_guaranteed_annual_income.aspx

8. Segal, H. Why Guaranteeing the Poor an Income Will Save Us All In the End. [Internet] [Updated 2013 June 8; cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/hugh-segal/guaranteed-annual-income_b_3037347.html

9. National Post. Andrew Coyne: Guarantee a minimum income, not a minimum wage [Internet] [Updated 2015 Jun 10; Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/canadian-politics/andrew-coyne-guarantee-a-minimum-income-not-a-minimum-wage

10. National Council of Welfare Reports. The Dollars and Sense of Solving Poverty. Volume #130. [Internet]. 2011 [Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/cnb-ncw/HS54-2-2011-eng.pdf

11. Statistics Canada. National Household Survey. Table 3.2 Low-income measures thresholds (LIM-AT, LIM-BT and LIM-MI) for households of Canada, 2010 [Internet]. 2016 [Updated 2016 Apr 1; cited 2016 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/ref/dict/table-tableau/t-3-2-eng.cfm

12. Corporation of the County of Wellington. 2014 Ontario works caseload profile. [Internet] [cited 2016 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.wellington.ca/en/socialservices/resources/Ontario_Works/2014_Caseload_Profile.pdf

13. Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. Ontario Nutritious Food Basket report. Guelph, Ontario; 2015.

14. Mikkonen J, Raphael D. Social determinants of health: the Canadian facts. Toronto: York University School of Health Policy and Management; 2010, 12.

15. Lightman E, Mitchell A, Wilson B. Poverty is making us sick: a comprehensive survey of income and health in Canada. The Wellesley Institute; 2008.

16. Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. Addressing social determinants of health in Wellington, Dufferin and Guelph: a public health perspective on local health, policy, and program needs. Guelph, Ontario; 2013

17. Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The spirit level: why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin Books; 2009.

18. Eggleton A, Segal H. In from the margins: a call to action on poverty, housing and homelessness. The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2009.

19. Segal, H. Scrapping Welfare: The case for guaranteeing all Canadians an income above the poverty line. Literary Review of Canada. [Internet]. 2012 [Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2012/12/scrapping-welfare/

20. Liberal Party of Canada. Resolution 100. [Internet].[Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.liberal.ca/policy-resolutions/100-priority-resolution-creating-basic-annual-income-designed-implemented-fair-economy/

21. Globe and Mail. Guaranteed income has merit as a national policy, minister says. [Internet]. [Updated 2016 Feb 5; Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/guaranteed-income-has-merit-as-a-national-policy-minister-says/article28588670/

22. Canadian Public Health Association. Public health matters: basic income guarantee. [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Feb 04]. Available from: http://www.cpha.ca/en/election2015/1.aspx

23. Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW). Promoting equity for a stronger Canada: the future of Canadian social policy; 2014.

24. Canadian Medical Association. Resolutions Adopted (confirmed) 148th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Medical Association Aug. 24-26, 2015. Halifax, NS. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/about-us/gc2015/resolutions-passed-at-gc_final_english.pdf

25. Forget, E., Equalizing opportunity: Can a guaranteed annual income help level the playing field for kids? Presentation at St. Michaels Hospital, Toronto, ON.

26. Globe and Mail. Liberals invite guaranteed-income expert to speak at pre-budget hearings. [Internet]. [Updated 2016 Feb 19; Cited 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/ottawa-invites-guaranteed-income-expert-to-speak-at-pre-budget-hearings/article28806760/

27. Ontario. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario public health standards. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2008 [revised 2014 May 1; cited 2014 May 1]. Available from:

http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/ophs_2008.pdf [PDF].