Key Points

Key points of this report are as follows:

In general, there was a rising trend in the rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph (WDG) over the past ten to eleven years, reflecting trends in STIs throughout Canada, North America and Europe.

There were more female than male cases of chlamydial infection, with the 20-29-year age group showing the highest incidence followed by teens 15-19 and with a sharp increase seen in 2018 among 20-29 year olds. The incidence of this STI was noticeably higher in urban areas of WDG. No condom use and heterosexual contact were the two most frequently reported sexual practices among cases of chlamydial infection, with same-sex contact only reported by a small percentage of cases annually.

In contrast to chlamydial infection, there were more male than female cases of gonorrhea. This STI showed a similar age profile to chlamydial infection, with the same sharp increase in 20-29-year age group in 2018. There was a steady increase in the incidence of this STI over the past 11 years, with a sharper increase in the last 5 years. Guelph experienced the highest incidence and the rest of Wellington the lowest, with no noticeable difference between rural and more urban areas of Dufferin. As seen for chlamydial infection, no condom use and heterosexual contact were the most commonly reported sexual practices, but a noticeably higher percentage of cases interviewed reported same-sex contact than for chlamydial infection, with a generally increasing trend in this practice seen for gonorrhea cases over the past five years.

Infectious syphilis was the least commonly reported STI in WDG. The vast majority of cases were male; only about 10% of cases in each of the last 3 years were female. The age group with the highest incidence was the 20-29-year olds, followed by 30-49 year olds, with no cases reported in teens 15-19 over the past five years. In contrast to chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, most of the cases interviewed who provided information about same-sex vs. opposite sex contact reported that sexual contact had been with the same sex; only a few cases reported heterosexual contact. This reflects the trend in North America, over the past few years, of infectious syphilis emerging among men who have sex with men (MSM).1

For all three diseases, WDG rates were consistently lower than provincial rates throughout the past eleven years.

No condom use is a risk factor for STIs.2 Data from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) conducted by Statistics Canada showed that in 2014, 28.3% of WDG respondents and 32.7% of Ontario respondents said that they had not used a condom when they had last had sex. In 2016, these percentages were 72.9 and 62.9% respectively. This possibly indicates a rising trend in this sexual practice, which is reflected in data collected during WDGPH STI case follow-up interviews.

Having multiple sexual partners is another recognized risk factor for STIs.2 In the CCHS 2012 survey, 16.0% of sexually active males and 9.9% of sexually active females in WDG reported having had more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months, up from 11.1% and 8.1% respectively in 2005.In 2016, these percentages were lower than in 2012 and for males, they were also lower than in 2005: 6.8% of males and 8.3% of females had had more than partner. Provincially in the 2012 survey, these percentages were 14.5% and 9.0% in males and females respectively, while in 2016, as in WDG, they were lower: 11.2% of males and 6.9% of females had had more than one partner in the past 12 months. This appears to show a relatively recent decrease in the percentage of the population, with more than one partner in a year for both males and females; however, it remains to be seen whether this trend will continue.

Introduction

Sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) are infections with organisms that are passed from one person to another by sexual contact. Diseases caused by such organisms include chlamydial infection, syphilis, gonorrhea and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, which can progress to the illness Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

The Community Health and Wellness Division of Wellington Dufferin Guelph Public Health (WDGPH) includes the Clinical Services Program. In addition to travel and general immunization clinics, program services include sexual health clinics, counselling and outreach services, harm reduction, and sexual health promotion and education. Sexual health clinics are serviced by public health nurses (PHNs) and physicians, and provide birth control counselling, pregnancy testing, and provision of emergency contraception, as well as testing, counselling and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

In Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph (WDG), as well as in the province of Ontario and in North America, chlamydial infection is the reportable disease with the highest incidence. The incidence of STIs has also been increasing in developed countries for several years. Approximately 6% of sexually active WDG respondents to the 2011-2012 Canadian Community Health Survey reported that they had been diagnosed with an STI at some point in the past. This was very similar to the provincial estimate; 5.4% of sexually active Ontario respondents had been diagnosed with an STI.3 In the 2016 survey, 4.3% of WDG and 6.0% of Ontario respondents reported that they had had an STI.

In this report, indicators of sexual health and well-being in WDG are summarized in order to give a snapshot of sexual health and safe sex practices in the community over the past few years. The report examines trends in the incidence of reported STIs in the area over recent years, with a focus on the two most common reportable STIs, chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, as well as infectious syphilis. Information collected on sexual practices from cases of each disease are also summarized, in order to examine any trends that may have occurred over the past five years. The key points in the previous section summarize the content that is given in more detail below.

In general, the data summarized in this report reflect an increasing incidence in all three diseases over the past several years, which is consistent with trends seen provincially, nationally and and throughout North America and several developed countries. Information presented here on sexual practices indicates that there seems to have been an increase in the practice of unprotected sex (without a condom), and also reflects the re-emergence of syphilis within the community of men having sex with men (MSM).

Section 1: Chlamydial Infection

What is Chlamydia?

Chlamydia is a disease caused by a microscopic parasite, Chlamydia trachomatis, which lives in the cells of an infected person. It is most often sexually transmitted and can cause infertility.

How is Chlamydia infection transmitted?

Chlamydia trachomatis is usually passed from one person to another through sexual intercourse. Like any sexually transmitted infection, a person’s risk of acquiring the infection increases with the number of sexual partners one has. However, unprotected sexual contact with one infected person can be enough to acquire the infection. Chlamydia is the most prevalent sexually-transmitted infection in Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph, in Ontario and in Canada.

What are the symptoms of Chlamydia infection?

Symptoms of Chlamydia infection usually begin within one to three weeks after sexual contact with an infected person. Men may experience a burning feeling while urinating, discharge from the penis or anus, or pain or tenderness in the testicles and rectal area. Women with symptoms often feel a burning sensation while urinating, and pain in the vagina or rectum, including during sexual intercourse. In women, there may also be a discharge from the vagina or anus.

In women, Chlamydia infection may cause inflammation of the cervix, and if untreated, can also spread to the uterus and fallopian tubes, causing infertility.

As many as one in four men and one in three women with Chlamydia infection do not develop any symptoms. However, an infected person can transmit the infection to a sexual partner even if they haven’t experienced any symptoms.

How can someone avoid getting Chlamydia infection?

Steps that can be taken to prevent acquiring Chlamydia include:

- Using a condom or dental (oral) dam, avoiding sharing sex toys, or abstaining from sexual intercourse.

- Having a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner, that is, having sex with only one person who is not infected with Chlamydia, and who is not having sex with anyone else.

Men or women at risk of becoming infected should be tested regularly for Chlamydia to avoid developing complications of the disease, and also to avoid spreading the infection to sexual partners. Any partners of a person who has tested positive should also be tested, and treated if infected.

1.1 Rates: 2008-2018:

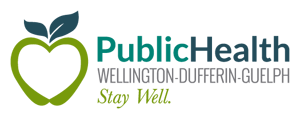

For over ten years, a general increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed chlamydial infections in Ontario and in Canada overall has been observed.4,5 The chart in Figure 1 demonstrates this trend; in each year since 2008 except 2012 and 2013, the crude rate (not adjusted for age) of reported cases of the infection was higher than it had been in the previous year. This trend was generally mirrored in WDG.

Figure 1: Crude Rates of Chlamydial Infection, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2008-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|

No. of Cases (WDG) |

371 | 466 | 519 | 626 | 555 | 475 | 612 | 646 | 737 | 691 | 818 |

| Rate per 100,000 WDG | 138.6 | 173.3 | 191.4 | 229.1 | 200.9 | 170.5 | 217.1 | 226.1 | 253.9 | 234.2 | 273.3 |

| Rate per 100,00 Ontario | 293.5 | 221.7 | 255.1 | 274.6 | 272.5 | 255.9 | 263.0 | 283.0 | 299.3 | 313.9 | 331.0 |

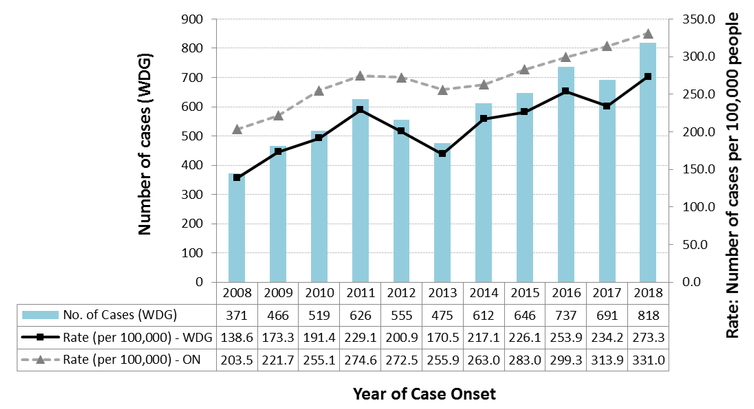

This increasing trend and similarity between provincial and local trends were evident even with adjustment of rates for the differing age profiles between the populations of Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario. This is shown in Figure 2, a chart of the age standardized rates for the two areas over the past five years (2014-2018).

Throughout the past eleven years (2008 to 2018), rates of reported chlamydial infection in Ontario have consistently been higher than those in WDG.

Figure 2: Age Standardized Incidence Rates of Chlamydial Infection, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2014-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| No. of cases (WDG) | 612 | 646 | 737 | 691 | 818 |

| Rate (WDG) | 217.6 | 228.4 | 258.3 | 240.5 | 283.7 |

| Rate (Ontario) | 267.16 | 289.60 | 307.00 | 322.58 | 342.72 |

1.2 Rates by age: 2014-2018:

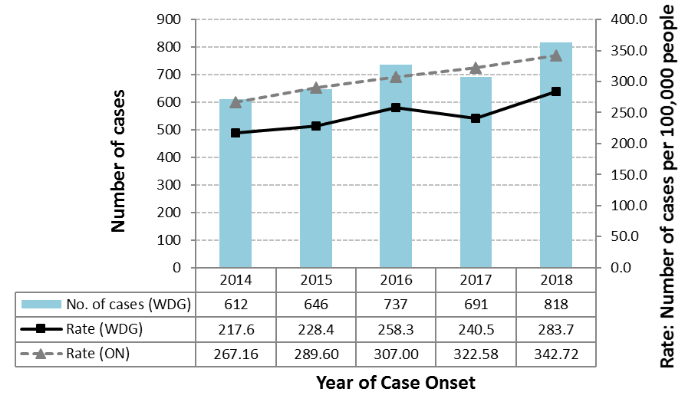

Comparison of incidence rates by age (Figure 3) over the past 5 years shows that rates in WDG have been highest in the 20-29-year age group, and second highest among teens 15-19 years of age. The third highest rates occurred in the 30-49-year age group, with rates in this age group being noticeably lower than those in the 15-19 and 20-29-year age groups. Relatively few cases were reported in other age groups, therefore these are not shown in the chart.

In 2018, a sharp increase occurred in the rate of reported chlamydial infections among 20-29-year-olds (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Age-Specific Rates of Chlamydial Infection, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph, 2014-2018

| Number of Cases per 100,000 People | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 15-19 years | 810.3 | 869.6 | 983.3 | 963.0 | 1079.9 |

| 20-29 years | 1287.7 | 1297.0 | 1358.9 | 1288.8 | 2199.4 |

| 30-49 years | 96.4 | 145.0 | 167.5 | 149.5 | 191.4 |

1.3 Rates by geography: 2014-2018:

Table 1 shows the rates of reported chlamydial infection in 2018 by region within WDG, sorted from highest to lowest rate, for the cases for which this information was available (775 cases). Guelph had the highest rate of reported cases (387 cases per 100,000 people), followed by Shelburne (332.3 cases per 100,000) and Orangeville (214.5 cases per 100,000). The rural areas of Dufferin and Wellington had noticeably lower rates than these relatively urban areas.

Table 1: Rates of chlamydial infection in regions within Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph. For each region, the population, number of cases and the rate per 100,000 people are shown in separate columns.

| Region | Population (2016 Census) | Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Guelph | 131,794 | 387.0 |

| Shelburne | 8,126 | 332.3 |

| Orangeville | 28,900 | 214.5 |

| Dufferin (minus Orangeville and Shelburne) | 24,709 | 170.0 |

| Wellington (minu Guelph) | 90,932 | 147.4 |

| Total WDG* | 284,461 | 272.4 |

*Excludes cases for which area of residence was unknown

This is consistent with previous (unpublished) reports summarizing rates of chlamydial infection by area, which have shown higher rates in the more urban areas of WDG, and relatively low rates in the rural area.

1.4 Rates by gender: 2014-2018:

The distribution of cases of chlamydial infections between males and females has been consistent across the past five years (2014-2018), with approximately 60% of cases in females and 40% in males each year. The higher rates in females are consistent with trends across North America and is thought to be due at least in part to a higher level of biological susceptibility to Chlamydia in females, as well as females being more likely to seek medical attention and to be screened for chlamydial infection.5

1.5 Sexual practices: 2014-2018:

Because of the sensitive nature of the information requested by Public Health during case follow-up interviews about sexual behaviours of cases, and because this information is self-reported by cases and unverified, any trends observed from analysis of this information should be interpreted with caution.

In 2018, 818 laboratory-confirmed cases of chlamydial infection were reported to WDGPH. The vast majority (86.3%) of the cases, when interviewed by Public Health, reported that they had had sex without a condom. Of those who reported having used a condom, some (29.1%) reported that the condom had broken during sex.

Most (75.7%) of the cases reported heterosexual contact, as opposed to sex with the same sex, which was reported by only 4.5% of cases; no information on heterosexual vs. homosexual contact was available for the remaining cases. Many (34.1%) of the cases said that they had had sex with a new contact within the previous two months, and 22.4% had had sex with more than one contact within the previous 6 months.

Other sexual behaviors or risk factors reported by cases included judgement having been impaired by alcohol or drugs (3.9% of cases), anonymous sex (2.7% of cases) and having met their sexual partner on the internet (2.4% of cases).

For most of these risk behaviours, there was no noticeable trend in the percentage of cases reporting the behaviours over the past five years (2014-2018). The exceptions were impairment of judgement by alcohol or drugs, which decreased from 9.8% and 10.1% in 2014 and 2015 respectively to only 3.9% in 2018, and sex without a condom, which showed a general upward trend from 64.0% of cases reporting this in 2014, to 93.3% and 86.3% in 2017 and 2018 respectively. In addition, there was general and gradual increase from year to year in the percentage of cases reporting same-sex contact, from 2.5% in 2014 to 4.5% in 2018, with the exception of a slight decrease in one year: from 3.5% in 2016 to 3.0% in 2017.

Section 2: Gonorrhea

What is gonorrhoea?

Gonorrhoea is a disease caused by a microscopic parasite, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which infects the lining of the reproductive and urinary systems.

How is the infection transmitted?

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is usually passed from one person to another through sexual intercourse. Like any sexually transmitted infection, a person’s risk of acquiring the infection increases with the number of sexual partners one has. However, unprotected sexual contact with one infected person can be enough to acquire the infection.

What are the symptoms of gonorrhoea infection?

Symptoms of gonorrhoea usually begin within one day to two weeks after sexual contact with an infected person. Many men with gonorrhoea do not experience any symptoms of the infection, but where symptoms occur, men may experience difficulty urinating and a discharge from the penis. Pain or tenderness in the testicles may also occur. Most women do not experience any symptoms, but if they do, difficulty urinating, increased vaginal discharge and bleeding between periods may occur. In men and women, infection in the rectum can cause discharge or bleeding from the anus, itching or soreness in the area, and painful bowel movements. The bacteria may also infect the throat during oral sex, which may or may not cause the symptom of a sore throat.

Women with or without symptoms may go on to develop serious complications of the infection, such as pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility. In men, infection may also cause infertility. In rare cases, the infection in either men or women may enter the blood and spread throughout the body, causing infections of the joints and skin. This condition, known as disseminated gonococcal infection, can be life-threatening.

The baby of a pregnant woman infected with gonorrhoea can become infected while passing through the birth canal during birth. This can cause blindness, joint infections or disseminated gonococcal infection in the child.

A person infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae can transmit the infection to a sexual partner even if they haven’t experienced any symptoms.

How can someone avoid getting gonorrhoea?

Steps that can be taken to prevent acquiring gonorrhoea include:

- Using a condom or dental (oral) dam, avoiding sharing sex toys, or abstaining from sexual intercourse.

- Having a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner, that is, having sex with only one person who is not infected with gonorrhoea, and who is not having sex with anyone else.

Men or women at risk of becoming infected or showing symptoms of the disease should be tested for gonorrhoea to avoid developing complications of the disease, and also to avoid spreading the infection to sexual partners. Any partners of a person who has tested positive should also be tested, and treated if infected.

2.1 Rates: 2008-2018:

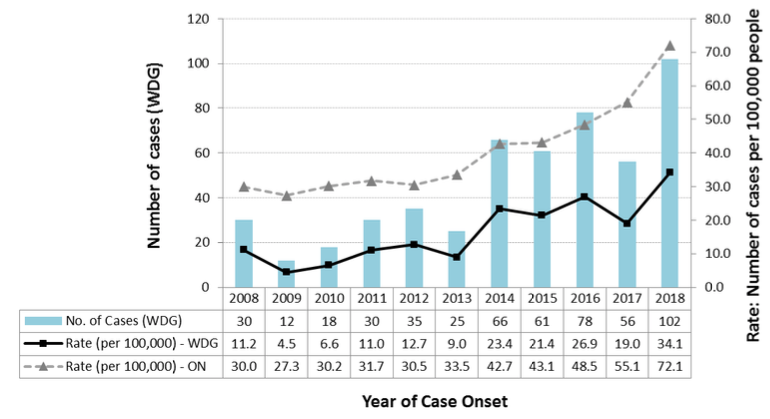

As for chlamydial infection, an increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea cases in Ontario and in Canada overall has also been observed over the past decade or more.4, 6 The chart in Figure 4 illustrates this trend; the crude rate (not adjusted for age) of reported gonorrhea showed a general upward trend from 2008 to 2018, with a sharper increase in this trend being apparent over the last five years. This trend was generally mirrored in WDG, with more fluctuations in the annual rates because of lower numbers of cases in WDG.

Figure 4: Crude Rates of Gonorrhoea Infections, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2008-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Onset | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| No. of cases (WDG) | 30 | 12 | 18 | 30 | 35 | 25 | 66 | 61 | 78 | 56 | 102 |

| Rate per 100,000 - WDG | 11.2 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 9.0 | 23.4 | 21.4 | 26.9 | 19.0 | 34.1 |

| Rate per 100,000 - Ontario | 30.0 | 27.3 | 30.2 | 31.7 | 30.5 | 33.5 | 42.7 | 43.1 | 48.5 | 55.1 | 72.1 |

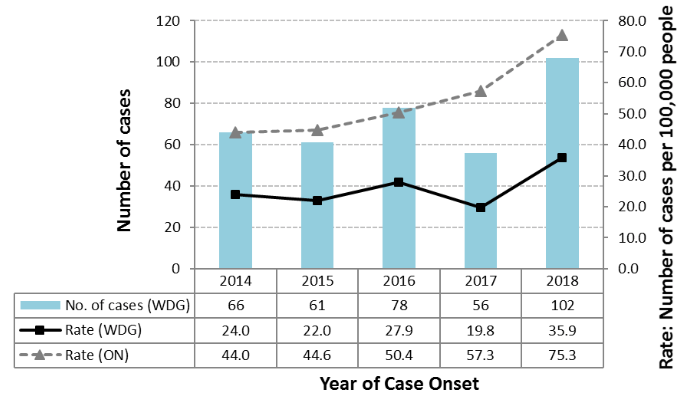

This increasing trend and similarity between provincial and local trends were evident even with adjustment of rates for the differing age profiles between the populations of Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario. This is shown in Figure 5, a chart of the age standardized rates for the two areas over the past five years (2014-2018). The general increase in the age-standardized rate in WDG was less consistent than in Ontario, with some fluctuation in rates from year to year - once again because of lower numbers of cases in WDG compared to Ontario.

Throughout the past eleven years (2008 to 2018), annual rates of reported gonorrhea in Ontario have consistently been higher than those in WDG.

Figure 5: Age Standardized Incidence Rates of Gonorrhoea, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2014-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| No. of cases (WDG) | 66 | 61 | 78 | 56 | 102 |

| Rate (WDG) | 24.0 | 22.0 | 27.9 | 19.8 | 35.9 |

| Rate (Ontario) | 44.0 | 44.6 | 50.4 | 57.3 | 75.3 |

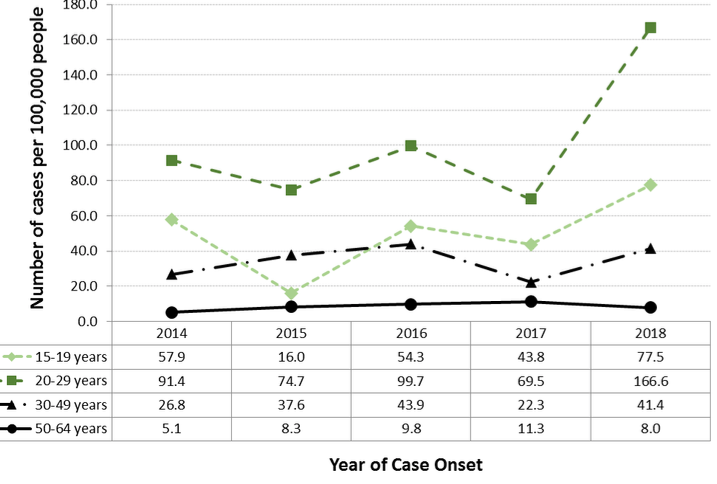

2.2 Rates by age: 2014-2018:

Comparison of incidence rates by age (Figure 6) over the past 5 years shows that rates in WDG have been highest in the 20-29-year age group, and second highest in all years except 2015 among teens 15-19 years of age. The third highest rates generally occurred in the 30-49-year age group, with rates in 50-64-year-olds being noticeably lower. Relatively few cases were reported in other age groups, which are therefore not shown in the chart.

As for chlamydial infection, 2018 saw a sharp increase in the rate of reported gonorrhea among 20-29-year-olds (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Age-Specific Rates of Gonorrhoea, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2014-2018

| Number of Cases per 100,000 people | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 15-19 years | 57.9 | 16.0 | 54.3 | 43.8 | 77.5 |

| 20-29 years | 91.4 | 74.7 | 99.7 | 69.5 | 166.6 |

| 30-49 years | 26.8 | 37.6 | 43.9 | 22.3 | 41.4 |

| 50-64 years | 5.1 | 8.3 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 8.0 |

2.3 Rates by geography: 2014-2018:

Table 2 shows the rates of reported gonorrhea in in 2018 by region within WDG, sorted from highest to lowest rate, for the cases for which this information was available (95 cases). As for chlamydial infection, Guelph had the highest rate of reported cases, followed by Shelburne; however, the rate in Shelburne was not very different from the rate in the rest of Dufferin County. The rate in rural Wellington County was approximately half of that in Dufferin.

Table 2: Rates of gonorrhea in regions within Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph. For each region, the population, number of cases and the rate per 100,000 people are shown in separate columns.

| Region | Population 2016 | Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Guelph | 131,794 | 53.1 |

| Shelburne | 8,126 | 24.6 |

| Dufferin (minus Orangeville and Shelburne) | 24,709 | 24.3 |

| Orangeville | 28,900 | 20.8 |

| Wellington | 90,932 | 12.1 |

| Total WDG* | 284,461 | 33.4 |

*Excludes cases for which area of residence was unknown

Because of the low numbers of cases reported in some regions, the above rates may be somewhat unstable, and any observed trends should be interpreted with caution.

2.4 Rates by gender: 2014-2018:

In four of the past five years (2014-2018), over 60% of reported cases of gonorrhea in WDG occurred in males and less than 40% in females. In 2016, there were also more cases in males than in females; however, males represented less than 60% of cases (53.6%) while 46.4% of cases occurred in females.

This trend was the opposite of that observed for chlamydial infection where, as mentioned, more cases were reported in females than in males. However, it was consistent with trends reported nationally for gonorrhea. This may reflect the rising rates of gonorrhea infection throughout North America in the population of men having sex with men (MSM).6

2.5 Sexual practices: 2014-2018:

Because of the sensitive nature of the information requested by Public Health during case follow-up interviews about sexual behaviours of cases, and because this information is self-reported be cases and unverified, any trends observed from analysis of this information should be interpreted with caution.

In 2018, there were 102 cases of laboratory-confirmed gonorrhea in WDG. One hundred of those cases (98.0%) reported when interviewed by Public Health that they had not used a condom during sexual contact. The majority of cases (56.9%) reported sex with the opposite sex, while 35.3% reported same-sex contact – a much higher percentage than for chlamydial infection. No information on heterosexual vs. homosexual contact was available for the remaining cases.

As for chlamydial infection, sexual activity with a new contact within the previous two months, and more than one sexual contact in the previous six months, were both commonly reported: 35.3% and 30.4%, respectively. Some cases (5.9%) said that they had met their sexual contact(s) through the internet, while judgement having been impaired by alcohol or drugs was reported by 3.9% of cases and anonymous sex by 2.0% of cases.

With the exception of 2015, when there was a slight decline in the percentage of cases reporting that they had not used a condom (from 62.1% in 2014 to 60.6% in 2015), there was an increase each year in the percentage reporting this sexual practice, rising to 65.4% in 2016, 92.0% in 2017 and finally 98.0% in 2018. The other risk behaviours showed no noticeable trend over the five-year period, with the percentages of cases reporting each behaviour fluctuating from year to year.

Section 3: Infectious Syphilis

What is syphilis?

Syphilis is a disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, which can infect the lining of the reproductive system and the mouth. From these, the bacterium can spread to other systems of the body, causing serious illness.

How is syphilis transmitted?

Syphilis bacteria are usually passed from one person to another through sexual intercourse; the organism is transmitted by contact with syphilis sores on the genitals or mouth of an infected person. Like any sexually transmitted infection, a person’s risk of acquiring the infection increases with the number of sexual partners one has. However, unprotected sexual contact with one infected person can be enough to acquire the infection.

What are the symptoms of syphilis?

Symptoms of syphilis begin an average of three weeks after sexual contact with an infected person, but can appear any time from 10 days to 13 weeks after. The first sign of infection is usually the appearance of a firm, painless sore (chancre), or several sores, at the point where the organism entered the body. Sores last three to six weeks. This period is referred to as the primary stage. At the end of this time, the sores usually heal whether or not the infection has been treated. However, if untreated, the infection remains in the body and goes on to produce further symptoms – in the secondary stage, then the latent and late stages of the disease.

In the secondary stage of syphilis, which can begin as the primary sore is healing or up to several weeks after, sores in the mouth, vagina or anus and rough, non-itchy skin rashes usually appear. The rash may include the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. There may also be fever, swollen lymph glands, sore throat, patchy hair loss, headaches, weight loss, muscle aches, and fatigue. Left untreated at this stage, the infection goes on to the dormant (latent) stage in which no symptoms are experienced, followed by the late stage of the disease with severe illness. The late stage of syphilis can develop as much as 10 to 20 years after the infection was first acquired. In this stage, the organs of the body show signs of damage, causing difficulty coordinating muscle movements, paralysis, numbness, gradual blindness, dementia and sometimes death.

At any stage of the disease, the syphilis infection may spread to the nervous system, causing altered behaviour and problems with movement and coordination. In addition, infection acquired by a woman during pregnancy can result in stillbirth, death of the baby shortly after death, or infection in the newborn that can develop into severe illness and death within a few weeks after birth.

A person infected with the primary, secondary or early latent stage of syphilis (known as infectious syphilis) may transmit the infection to a sexual partner even if they have not had any noticeable symptoms.

How can someone avoid getting syphilis?

Steps that can be taken to prevent acquiring syphilis include:

- Using a condom or dental (oral) dam, avoiding sharing sex toys, or abstaining from sexual intercourse.

- Having a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner, that is, having sex with only one person who is not infected with syphilis, and who is not having sex with anyone else.

- Exercising caution even when having sex with a condom; contact with the syphilis sores of an infected partner that are not covered by a condom can allow the disease to be transmitted.

Men or women at risk of becoming infected or showing symptoms of the disease should be tested for syphilis to avoid developing complications of the disease, and also to avoid spreading the infection to sexual partners. Any partners of a person who has tested positive should also be tested, and treated if infected.

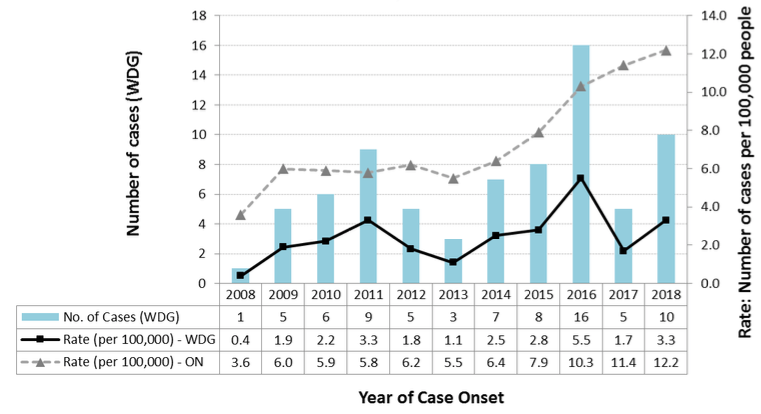

3.1 Rates: 2008-2018:

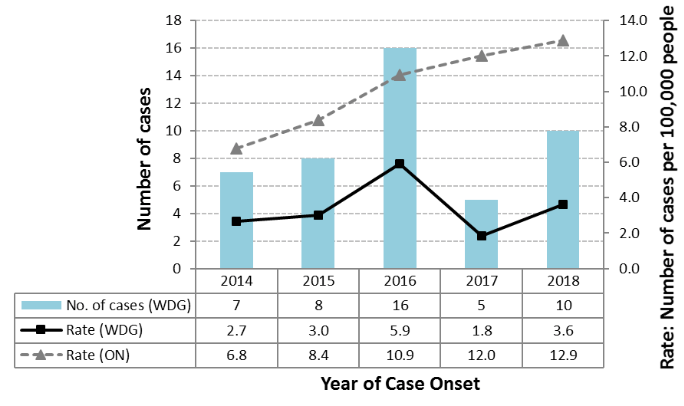

As for chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, there has been a noticeable increase in the annual crude rates of laboratory confirmed infectious syphilis over the past few years, reflecting trends seen throughout North America.4 For infectious syphilis, this rise has been marked since 2013, with the provincial rate increasing from 5.5 cases per 100,000 people in 2013 to 12.2 cases per 100,000 in 2018. Annual rates of this disease in WDG have shown a less steady trend; while the rate of cases each year is now generally higher than rates in the early 2000s, this has been driven more by sharp increases in some years rather than consistent year-to-year increases (Figure 7). The marked fluctuation in rates in WDG may be due at least in part to the relatively low numbers of cases of this disease reported in the region compared to the other sexually transmitted infections covered in this report, which produces statistically unstable rates. Any trends observed in the annual rates should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Figure 7: Crude Rates of Infectious Syphilis, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontairo, 2008-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| No. of Cases (WDG) | 1 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 10 |

| Rate per 100,000 - WDG | 0.4 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 3.3 |

| Rate per 100,000 - Ontario | 3.6 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 10.3 | 11.4 | 12.2 |

Adjusting the local and provincial rates for any differences in age profiles between the two populations showed a similar pattern, with steadily increasing annual provincial rates and fluctuating rates in WDG with sporadic annual increases (Figure 8).

Throughout the past eleven years (2008 to 2018), as was the case for chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, annual rates of reported infectious syphilis in Ontario have consistently been higher than those in WDG.

Figure 8: Age Standardized Incidence Rates of Infectious Syphilis, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontairo, 2014-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| No. of cases (WDG) | 7 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 10 |

| Rate (WDG) | 2.7 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 1.8 | 3.6 |

| Rate (Ontario) | 6.8 | 8.4 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 12.9 |

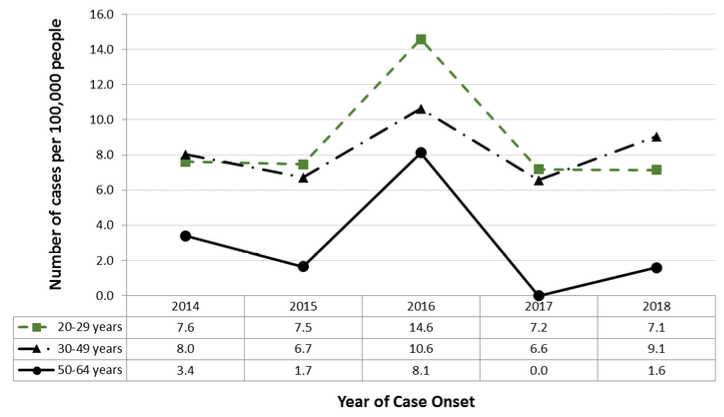

3.2 Rates by age: 2014-2018:

Comparison of incidence rates by age (Figure 9) over the past 5 years shows that compared to chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, the age range of cases has been higher, with most cases occurring in people 20 to 64 years of age. Rates of infectious syphilis in WDG in these years were highest in the 20-29-year age group, and in most years, second highest in the 30-49-year age group, with rates in 50-64 year-olds somewhat lower but noticeably higher than they were for chlamydial infection and gonorrhea. In contrast to chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, no cases were reported in teens aged 15 to 19 years. There were also few or no cases reported in the other age groups. Those age groups are therefore not shown in the chart.

Figure 9: Age-specific Rates of Infectious Syphilis, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontairo, 2014-2018

| Number of cases per 100,000 people | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 20-29 years | 7.6 | 7.5 | 14.6 | 7.2 | 7.1 |

| 30-49 years | 8.0 | 6.7 | 10.6 | 6.6 | 9.1 |

| 50-64 years | 3.4 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

3.3 Rates by geography: 2014-2018:

The low number of cases of infectious syphilis reported annually in WDG does not allow for any meaningful analysis of rates by county or other sub-region within WDG. As expected in view of the fact that the sub-region with the highest population is the city of Guelph, most cases each year from 2014-2018 were reported from this area, with cases reported only sporadically from other areas within WDG.

3.4 Rates by gender: 2014-2018:

The vast majority of cases of laboratory confirmed infectious syphilis reported in WDG over the past five years have been in males. In 2014 and 2015, all cases were in males, while in 2016, 2017 and 2018 about 90% of cases were in males. This reflects trends seen elsewhere in North America of riding rates of infectious syphilis in the MSM community.7

3.5 Sexual practices: 2014-2018:

Because of the sensitive nature of the information requested by Public Health during case follow-up interviews about sexual behaviours of cases, and because this information is self-reported be cases and unverified, any trends observed from analysis of this information should be interpreted with caution.

The low numbers of cases of infectious syphilis reported in WDG each year results in the amount of information provided by follow-up interviews being insufficient to allow for any meaningful analysis of trends in sexual practices reported by cases. However, among all cases of infectious syphilis reported over the five years (2014-2018 inclusive), the most commonly reported practice was sex with same sex; in fact, only 13.3% of cases interviewed reported heterosexual contact. The second most frequently reported practice was sex without a condom and the third was anonymous sex.

The predominance of males in the demographic breakdown of infectious syphilis cases in WDG, and the fact that, in contrast with chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, only a few interviewed cases reported sex with the opposite sex, reflects the findings of published surveillance reports that have described a re-emergence of infectious syphilis in North America driven primarily by an increasing incidence within the community of men having sex with men (MSM).4,7

Section 4: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

What is Human Immunodeficiency Virus?

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that can destroy infection-fighting white blood cells in infected people.

How is HIV transmitted?

HIV is usually passed from one person to another through contact with the blood or sexual body fluids of an infected person, such as through sexual intercourse, being born to an HIV-infected mother, sharing injection drug-taking equipment such as needles, or the transfusion of blood from an HIV-positive donor. Like any sexually transmitted infection, a person’s risk of acquiring the infection increases with the number of sexual partners one has. However, unprotected sexual contact with one infected person can be enough to acquire the infection.

What are the symptoms of HIV infection?

From 2 weeks to 3 months after a person has become infected, flu-like symptoms may occur, including fever, muscle aches, sore throat and fatigue. However, HIV infection very often produces no symptoms for several years, during which time the virus can nevertheless be passed on by the infected person. If left untreated, the infection eventually produces a disease called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), where the destruction of infection-fighting white blood cells by the virus causes reduced resistance to infectious diseases, eventually resulting in death. Timely treatment of HIV infection can delay the development in AIDS in an infected person; however, infection with the virus usually cannot be eliminated by currently available treatments.

How can someone avoid getting HIV?

Steps that can be taken to prevent acquiring HIV infection include:

- Using a condom or dental (oral) dam, avoiding sharing sex toys, or abstaining from sexual intercourse.

- Having a mutually monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner, that is, having sex with only one person who is not infected with HIV, and who is not having sex with anyone else.

- Abstaining from injection drug use.

- If injectable drugs are used, using clean needles and equipment when injecting.

Men or women at risk of becoming infected or showing symptoms of the disease should be tested for HIV to avoid developing AIDS, and also to avoid spreading the infection to sexual partners or unborn children. Any partners of a person who has tested positive should also be tested, and treated if infected. Beginning anti-HIV medication soon after exposure to the virus (e.g. soon after sex with an infected person) can in some cases prevent HIV infection from becoming established in the body.

The risk of transmission of infection to an unborn child by a pregnant mother who is HIV-positive may be reduced by early testing and treatment of the mother.

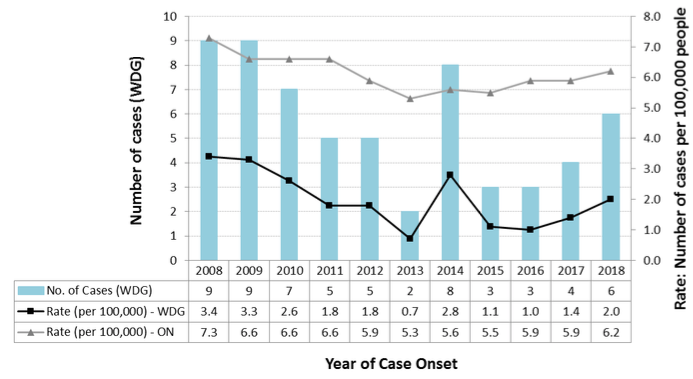

4.1 Rates: 2008-2018:

Of the STIs covered in this report, HIV infection accounted for the lowest number of cases in most years from 2008-2018, with a total of 24 confirmed cases reported to WDGPH over the past five years (2014-2018) – approximately half the number of cases of infectious syphilis reported in the same time period. Throughout that period, rates of HIV infection in WDG were consistently much lower than rates in the province overall (Figure 10), with the rates in WDG from year to year and no obvious increasing or decreasing trend. As in the case of infectious syphilis, the fluctuation in rates in WDG may be due at least in part to the relatively low numbers of cases of this disease reported in the region compared to chlamydial infection and gonorrhea, which can produce statistically unstable rates. Any trends observed in the annual rates should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Figure 10: Crude Rates of HIV Infections, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2008-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Onset | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| No. of Cases (WDG) | 9 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Rate per 100,000 (WDG) | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| Rate per 100,000 (Ontario) | 7.3 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.2 |

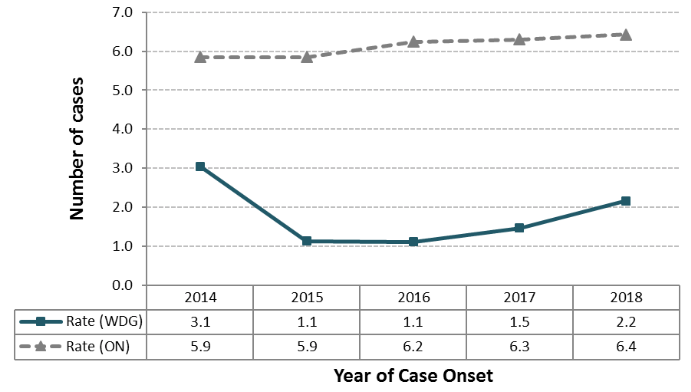

Adjusting the local and provincial rates for any differences in age profiles between the two populations showed a similar pattern, with steadily increasing annual provincial rates and fluctuating rates in WDG with sporadic annual increases (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Age Standardized Incidence Rates of HIV/AIDS, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2014-2018

| Number of Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Rate (WDG) | 3.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| Rate (Ontario | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

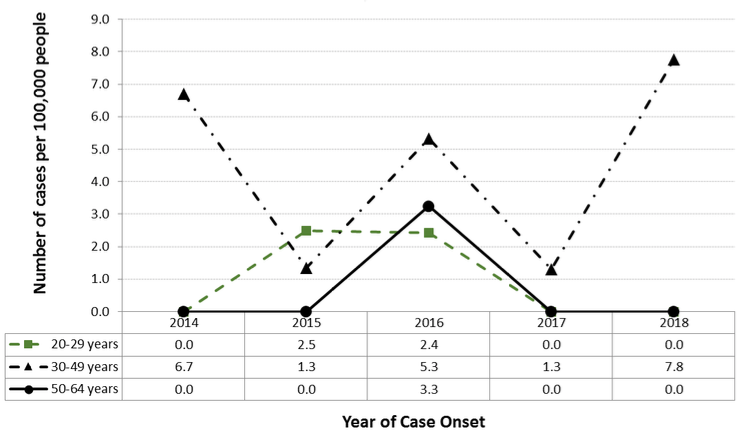

4.2 Rates by age: 2014-2018:

Most cases of HIV infection reported to WDGPH over the past five years occurred in people 20 to 24 years old, with this age group seeing the highest rates of the infection of all age groups in most years. However, cases also occurred in older age groups, including some in people aged 65 years and older (not shown).

No cases were reported in people under 20 years of age.

Figure 12: Age-specific Rates of HIV Infection, Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph and Ontario, 2014-2018

| Number of cases per 100,000 people | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Case Onset | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 20-29 years | 0.0 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 30-49 years | 6.7 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 7.8 |

| 50-64 years | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

4.3 Rates by geography: 2014-2018:

The low number of cases of HIV infection reported annually in WDG does not allow for any meaningful analysis of rates by county or other sub-region within WDG. As expected in view of the fact that the sub-region with the highest population is the city of Guelph, most cases each year from 2014-2018 were reported from this area, with cases reported only sporadically from other areas within WDG.

4.4 Rates by gender: 2014-2018:

Most (58.3%) cases of HIV infection reported in WDG over the past five years have been in males.

4.5 Sexual practices: 2014-2018:

Because of the sensitive nature of the information requested by Public Health during case follow-up interviews about sexual behaviours of cases, and because this information is self-reported be cases and unverified, any trends observed from analysis of this information should be interpreted with caution.

The low numbers of cases of HIV reported in WDG each year results in the amount of information provided by follow-up interviews being insufficient to allow for any meaningful analysis of trends in sexual practices reported by cases. However, among all cases of HIV reported over the five years (2014-2018 inclusive), the most commonly reported practice was sex without a condom and heterosexual contact. Same-sex contact was reported by 29.4% of cases for which this information was available. About the same percentage of cases interviewed reported that their contact was HIV positive, and approximately 23.5% reported that they had had sex with an anonymous partner.

Section 5: Sexual Practices in WDG: Canadian Community Health Survey

Behaviours and practices shown to increase the risk of contracting STIs include having multiple sexual partners and engaging in sexual activity without a condom.2

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) is a survey conducted at regular intervals by Statistics Canada to gather health-related data at various levels of geography within Canada. In the CCHS 2012 survey, 16.0% of sexually active males and 9.9% of sexually active females in WDG reported having had more than one sexual partner in the past 12 months, up from 11.1% and 8.1% respectively in 2005. In Ontario overall, these 2012 percentages were 14.5% and 9.0% respectively. In 2016, the percentage of respondents indicating that they had had more than one partner had decreased to 6.8% of males and 8.3% of females in WDG, and 11.2% of males and 6.9% of females provincially. These changes may be indicative of either a decreasing trend in the percentage of people with multiple sexual partners in recent years, or a fluctuating trend like that seen in the data collected by Public Health and described above in this report.

In 2014, 28.3% of WDG respondents and 32.7% of Ontario respondents said that they had not used a condom when they had last had sex, while in 2016, these percentages had increased to 72.9% and 62.9% in WDG and Ontario, respectively. This appeared to show a rising trend in the practice of having unprotected sex, which may be reflected in data collected by Public Health during STI case follow-up interviews.

Although it is recognized that the practice of seeking sexual partners via the internet appears to have become more prevalent in recent years, it is unclear how prevalent this practice is locally and in Ontario. The CCHS does not include this question, so does not provide any information on the practice, and published studies on the prevalence of and risks associated with the practice are sparse, with at least one systematic review finding no evidence of increased risk of STIs associated with it.8 As mentioned in previous sections of this report, a proportion of cases of STI followed up by Public Health indicate that they had met their partner via the internet; however, no clear year-to-year trend could be identified, with the percentage of cases reporting this practice fluctuating over the five-year period (2014-2018).

Discussion and Conclusion

This report illustrates the increasing incidence in STIs, generally, over the past several years that reflects provincial, national and North American trends, as well as a trend that has been seen for some time now in several other developed countries. Factors thought to explain this trend, at least in part, include more accurate tests, namely nucleic acid amplification tests, being available for STIs.5,6,7 Increased screening for oropharyngeal and rectal gonorrheal infections may have contributed to the rising rates of that disease.6 There are, however, many behavioural risk factors for STIs, and it is often difficult to gather accurate information on changing behavious in a population that may be behind rising rates of STIs. Information on sexual practices from WDG data indicates that there seems to have been an increase in the practice of unprotected sex (without a condom), with continued occurrence of other practices known to increase the risk of contracting an STI. The demographic breakdown of infectious syphilis cases, and the fact that only a small percentage of the cases interviewed during case follow-up reported heterosexual contact, reflects the re-emergence of syphilis within the community of men having sex with men (MSM).7

More detailed information on factors thought to be contributing to the rise of STIs in Canada is available in literature listed in the references;4,5,6,7 however, although some or all of the factors postulated there may apply to the local situation in WDG, it would be difficult to conclude this with any degree of certainty; therefore, any such conclusions should be made with caution.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/2017-STD-Surveillance-Report_CDC-clearance-9.10.18.pdf

- Wilson Chialepeh N and Sathiyasusuman A. Associated Risk Factors of STIs and Multiple Sexual Relationships among Youths in Malawi. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015;10(8):e0134286. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4527764/

- Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health. Health Status Report: Sexual and Reproductive Health in WDG. 2015. [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available at: https://www.wdgpublichealth.ca/sites/default/files/file-attachments/report/hs_report_2015-overview-of-sexual-and-reproductive-health-in-wdg_access.pdf

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on Sexually Transmitted Infections in Canada: 2011.Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada. 2014. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/64-02-14-1200-STI-Report-2011_EN-FINAL.pdf

- Choudhri Y, Miller J, Sandhu J, Leon A, Aho J. Chlamydia in Canada, 2010-2015. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2018 Feb;44(2):49-54.[cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5864312/

- Choudhri Y, Miller J, Sandhu J, Leon A, Aho J. Gonorrhea in Canada, 2010-2015. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2018 Feb;44(2):37-42. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5933854/

- Choudhri Y, Miller J, Sandhu J, Leon A, Aho J. Infectious and congenital syphilis in Canada, 2010-2015. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2018 Feb;44(2):43-48. [cited 2019 Feb 14]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5864261/

- Tsai JY, Sussman S, Pickering TA, Rohrbach LA. Is Online Partner-Seeking Associated with Increased Risk of Condomless Sex and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Individuals Who Engage in Heterosexual Sex? A Systematic Narrative Review. Arch Sex Behav. 2019 Feb;48(2):533-555.